Risk Assessment Studies

Report No. 77

Iodine in Food

March 2025

Centre for Food Safety

Food and Environmental Hygiene Department

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

Correspondence:

Risk Assessment Section

Centre for Food Safety,

Food and Environmental Hygiene Department,

43/F, Queensway Government Offices,

66 Queensway, Hong Kong.

Email: enquiries@fehd.gov.hk

| Contents |

|---|

| Executive Summary |

|

1. Objectives |

| 2. Background |

| 3. Scope of Study |

| 4. Methodology |

| 5. Results and Discussions |

| 6. Conclusion and Recommendation |

| References |

| Appendix: Iodine contents (μg/100g) detected in food samples |

Risk Assessment Studies

Report No.77

Iodine in Food

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Iodine is an essential micronutrient required for normal thyroid function, growth, and development. Its deficiency and excess both have adverse consequences on the body through effects on the thyroid gland. Across the life-span, adverse health effects of iodine deficiency disorders (IDDs) include damage to the developing brain, goitre (an enlarged thyroid gland) and hypothyroidism. Pregnant, lactating women, infants, and young children are particularly vulnerable to IDDs.

2. In Hong Kong, the Iodine Survey and the Population Health Survey 20-22 by the Department of Health measured spot urine iodine with the median urinary iodine concentration of respondents as an indicator. These surveys reveal that the iodine status was adequate in school-aged children aged 6-12, the younger people aged 15-34, child-bearing age women aged 15-44, and pregnant women who were taking supplements containing sufficient iodine. However, lactating women and the general population aged 15-84 overall had insufficient iodine intake and mild iodine deficiency.

3. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily iodine intake of 120μg for children aged 6-12, 150μg for adolescents and adults, and 250μg for pregnant or lactating women. The WHO opines that the best way to prevent micronutrient malnutrition is to ensure consumption of a balanced diet that is adequate in every nutrient. The long-term measures for the prevention and control of micronutrient deficiencies (e.g., iodine) should be based on diet diversification and consumer education about choosing foods that provide a balanced diet.

4. The objective of this study is to examine the iodine levels in iodine-rich foods available in the local market. The results supplement the information on iodine contents in locally available foods in the Dietary Iodine Intake in Hong Kong Adults risk assessment study report (RA Study 2011) by the Centre for Food Safety (CFS) in 2011.

5. Between July and October 2023, a total of 296 prepackaged and non-prepackaged food samples covering 10 food groups were collected. The first five food groups were food known to be high in iodine from the RA Study 2011 and literature: (1) “Plain seaweed”, (2) “Fish and its products”, (3) “Aquatic animals (other than fish) & their products”, (4) “Eggs”, and (5) “Dairy & its products”. The other five food groups were foods containing high-iodine ingredients, including kelp/seaweed and seafood: (6) “Soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)”, (7) “Rice rolled with seaweed”, (8) “Soup with seaweed”, (9) “Snacks with seaweed”, and (10) “Miscellaneous”.

6. The food samples were collected from various premises including restaurants, supermarkets, dry goods stores, fresh provision shops, and food stores selling seaweed-containing food (e.g., sushi bars, noodles shops, dessert shops) in different locations on Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories and from online platforms. The iodine contents were determined by the CFS’s Food Research Laboratory.

7. The iodine contents of the food samples ranged from not detected (i.e., <0.2μg/100g) to 220,000μg/100g. Similar to RA Study 2011, a large variability of iodine contents is found in foods belonging to the same group. Based on the mean values, the food group “Plain seaweed” outstands the others as almost all of its food items contain iodine above 600μg/100g. It is followed by the food group “Aquatic animals (other than fish) & their products”, with nearly half of its food items containing iodine above 200μg/100g. The top five food items with the highest iodine contents (in descending order) per 100g are: (1) Dried kelp (180,000μg), (2) Dried seaweed (including seaweed wrapper) (4,000μg), (3) Dried crab snack (1,700μg), (4) Seasoned seaweed snacks (1,600μg), and (5) Seaweed flakes/powder toppings (980μg).

8. Eggs, seawater fish, crustaceans, molluscs, dairy and their products are also good sources of iodine. In the context of a healthy balanced diet, adults could consume more of these to meet their dietary iodine requirement of 150μg/day. For example, a fillet of “raw mackerel” (90g) (median 71µg/100g), a portion of “sea urchin” (20g) (median 360µg/100g), a chicken egg (50g) (median 37µg/100g), three quail eggs (30g) (median 120µg/100g), or a glass of “cow milk” (240ml) (median 20µg/100g) will meet 43%, 48%, 13%, 24% and 32% of the daily iodine requirement, respectively.

9. This 150μg/day requirement could also be met by including a variety of foods added with seaweeds. For example, a portion of “Korean soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)” (200g) (median 73µg/100g), a bowl of “Chinese seaweed soup” (200g) (median 83µg/100g), a portion of “Kimbap” (250g) (median 57µg/100g), or a portion of “Warship roll (Gunkan-maki)” (250g) (median 54µg/100g) will meet 97%, 111%, 95%, and 90% of the daily iodine requirement, respectively.

Conclusion and Recommendations

10. Iodine is present in many locally available foods. High iodine foods include seaweeds such as kelps, seafood such as fish and prawns, eggs, dairy, and their products. Foods using seaweeds as ingredients are also good sources of iodine, e.g., noodle dishes, rice dishes, soup dishes and bakery wares.

11. Consumers can increase iodine intake by including high iodine food into the diets or adding iodine-rich ingredients according to their dietary practices.

Advice to the public

12. The public is recommended to maintain a healthy and balanced diet and to consume foods that are rich in iodine, including seaweeds such as kelp; seafood such as fish and prawns; eggs; dairy; and their products, so as to meet the WHO’s daily iodine intake recommendation:

- According to the Joint Recommendation by the Working Group on Prevention of Iodine Deficiency Disorders, members of public are advised to consume foods that are rich in iodine as part of a healthy, balanced diet and use iodised salt instead of ordinary table salt, keeping total salt intake below 5 g (1 teaspoon) per day.

- During food preparation, include iodine-rich ingredients to enhance the iodine content of different foods (e.g., rice, noodles, soup, bakery, vegetarian food, beverages, and desserts) in the diet. Examples of iodine-rich foods or ingredients are seafood (e.g., seaweed or kelp, marine fish, crustaceans, molluscs), eggs, dairy, and their products.

- When choose snacks, consider those containing high iodine content, like ready-to-eat seaweed, boiled quail eggs, and dried seafood snacks (e.g., cuttlefish, shrimp, fish), etc..

- Persons with existing medical conditions or thyroid problems are advised to consult healthcare professionals concerning the intake of iodine.

1 Objective

This study aims to examine the iodine levels in iodine-rich foods (both non-prepackaged and prepackaged) available in the local market. It supplements the information on iodine contents in locally available foods reported by the Centre for Food Safety (CFS) in the Dietary Iodine Intake in Hong Kong Adults risk assessment study report in 2011 (RA Study 2011), which facilitates consumers to make food choices to increase iodine intake from the diet.

2 Background

2. Iodine is an essential trace element that is present in the thyroid hormones, thyroxine, and triiodothyronine. It is required for normal thyroid function, growth, and development. Its deficiency and excess both have adverse consequences on the body through effects on the thyroid gland. Across the life-span, adverse health effects of iodine deficiency disorders (IDDs) include damage to the developing brain, goitre (an enlarged thyroid gland), hypothyroidism, etc. Pregnant, lactating women, infants, and young children are particularly vulnerable to IDDs.1,2 The iodine status of pregnant women and women of reproductive age are a recognised international concern. This is because for the developing foetus, iodine deficiency is one of the greatest causes of preventable intellectual disability, and mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency in women could be associated with long-lasting effects on child cognition.

3. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily intake for iodine of 120μg for children aged 6-12, 150μg for adolescents and adults, and 250μg for pregnant and lactating women. The WHO opines that the best way of preventing micronutrient malnutrition is to ensure consumption of a balanced diet that is adequate in every nutrient. The long-term measures for the prevention and control of micronutrient deficiencies (e.g., iodine) should be based on diet diversification and consumer education about how to choose foods that provide a balanced diet, including the necessary vitamins and minerals (such as iodine).3,4

2.1 Iodine status worldwide and among the local population

4. According to the Iodine Global Network (IGN) Global Scorecard, the effective collaboration among national governments, international and civil society organisations and the salt industry has brought the number of countries with insufficient iodine status down from 113 in 1993 to 21 in 2021. IGN considers that the work to keep iodine deficiency at bay has been a public health success story.5 Having said that, iodine is still one of the most common nutrient deficiencies and is estimated to affect 35-45% of the world’s population.6

5. There is evidence that some sub-populations (e.g., pregnant and lactating women) in Hong Kong may not get enough iodine through diet. The Department of Health (DH) has conducted some studies and surveys related to the iodine status of the population using a well-accepted, cost-efficient and easily obtainable indicator for iodine status recommended by the WHO – urinary iodine concentration (UIC).7

6. Urinary iodine is a priority indicator for the assessment of iodine intake and status in populations and is assessed from spot or 24-hour urine samples in field studies and surveys. The use of UIC is an indicator of recent iodine intake and status.8 The 24-hour UIC is considered the gold standard in this field.9 The Iodine Survey Report released in 2021 by the DH shows that the iodine status of school-aged children aged 6-12 based on the spot urine iodine test result was adequate (i.e. 100-199μg/L), but that of pregnant and lactating women was insufficient (i.e. <150μg/L and <100μg/L, respectively); however that of pregnant women taking adequate iodine-containing supplement was adequate (i.e. 150-249μg/L).10

7. The DH’s Report of Population Health Survey 2020-22 (PHS 2020-22 Report) covers the dietary habits related to iodine intake and the iodine status of Hong Kong people aged 15-84.11 Part 1 of the PHS 2020-22 Report reveals that less than 10% of persons aged 15 or above eat seaweeds at least once a week on average.12 Moreover, the Thematic Report on Iodine Status of PHS 2020-22 indicates insufficient iodine intake and mild iodine deficiency status among the general population aged 15-84. However, the iodine status of the younger people (aged 15-34) and child-bearing age women (aged 15-44) were adequate.13 The Thematic Report on Iodine Status also reveals that the median UIC of respondents who ate seaweed at least once per week were significantly higher than those who ate less than once per week.

2.2 Educating the public to consume a variety of iodine-rich foods

8. The Thematic Report on Iodine Status urges for health education to raise awareness of iodine intake and consuming food with more iodine as part of a healthy balanced diet. Meanwhile, the Working Group on Prevention of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (Working Group) set up in 2021 by the DH and CFS endorsed the “Joint Recommendation on Iodine Intake for the Members of the Public” (the Joint Recommendation). The important ways to maintain adequate iodine nutrition stated in the Joint Recommendation includes “Consume food with more iodine as part of a healthy balanced diet. Seaweed, kelp, seafood, marine fish, eggs, milk, dairy products are food rich in iodine.” The Joint Recommendation also advocates the use of iodised salt instead of ordinary table salt, keeping total salt intake below 5g (1 teaspoon) per day. Besides, additional measures of taking iodine-containing supplements containing at least 150μg is recommended for the pregnant and lactating women.

2.3 Dietary sources of iodine and iodine contents in local food

9. The earth’s soils contain varying amounts of iodine, which in turn affects the iodine content of crops. On land, it is known that food such as most fruits and vegetables are poor sources of iodine, and the amounts they contain are affected by the iodine content of the soil, fertiliser use, and irrigation practices. This variability affects the iodine content of meat and animal products because of its impact on the iodine content of foods that the animals consume. Furthermore, the amount of iodine in egg and dairy products varies by whether the animals received iodine feed supplements, and whether iodophor sanitising agents were used to clean the milk-processing equipment. In the sea, fish and crustaceans of marine origin, seaweeds, and sea vegetables accumulate iodine from seawater, and they are the richest food sources of iodine food. However, the iodine content of seaweed varies with different species; it is generally greater in brown seaweeds (kelps) than the green or red varieties.

10. A comprehensive study on iodine levels in food was conducted by CFS in 2011 which reported that the effects of cooking on the loss of iodine was minimal except for boiling.14,15 The RA Study 2011 has covered many food groups, including those known to have low iodine contents (e.g., water, meat, poultry, cereal/grains and vegetables). In the RA Study 2011, generally speaking, the iodine content in kelp (ranged from 200,000 to 290,000μg/100g) was much higher than that in other seaweeds (ranged from 84 to 22,000μg/100g), the iodine content in freshwater fish (ranged from 0.4 to 3μg/100g) was much lower than that in seawater fish (ranged from 5 to 60μg/100g), and the iodine content in egg yolk (ranged from 20 to 230μg/100g) was higher than in the whole egg (ranged from 8.2 to 43μg/100g).

11. Due to resource consideration, the RA Study 2011 covered only some common foods high in iodine content. Certain foods that may have high iodine contents like Chinese soup noodles containing seaweed and rice-balls containing seaweed were not covered.

3 Scope of Study

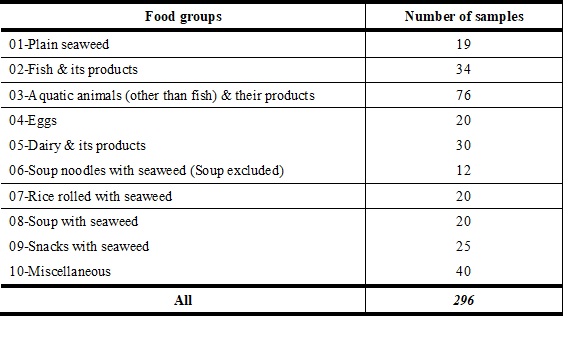

12. This study covered 10 food groups and a total of 296 food samples were collected. Table 1 below listed out the number of samples covered in the 10 food groups (items in each food group are listed in the Appendix).

Table 1. Food groups and number of samples covered in the study.

13. The first five food groups belonged to the major food groups that were found to have high iodine contents in the RA Study 2011 and some overseas studies, namely (1) “Plain seaweed”, (2) “Fish and its products”, (3) “Aquatic animals (other than fish) & their products”, (4) “Eggs”, and (5) “Dairy & its products”. The remaining five food groups are foods containing high-iodine ingredients, particularly seaweed/kelp, which include: (6) “Soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)”, (7) “Rice rolled with seaweed”, (8) “Soup with seaweed”, (9) “Snacks with seaweed”, and (10) “Miscellaneous”. Food items in the “Miscellaneous” group include “Seaweed flakes/powder toppings”, “Cabbage Kimchi”, “Bakery with seaweed”, beverages or desserts with seaweed, etc.

4. Methodology

4.1 Sampling

14. Food matching at least one of the below sampling criteria had been included in the sampling list: a) Food with relatively high iodine contents (based on previous CFS’s research, literature, and food composition databases); b) Food with relatively high consumption amount based on the Second Hong Kong Population-based Food Consumption Survey (2nd FCS16); and c) Food with high iodine ingredients (e.g., kelp/seaweed, seafood, iodised salt) in food menus or on the food labels of prepackaged food.

15. Sampling was conducted between July and October 2023. They were collected from various local premises, e.g., restaurants, supermarkets, dry goods stores, fresh provision shops, grocery stores, wet market stalls, sushi bars, noodles shops, dessert shops, etc. in Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories as well as samples purchased via online platforms. A total of 296 food samples were collected to compile 16 sub-groups and 66 food items in the sampling list. Three to five samples were collected for each food item.

4.2 Laboratory analysis and data collection

16. Laboratory analysis was conducted by the Food Research Laboratory (FRL) of the CFS. Only the edible portions of all food samples were analysed individually for iodine content using an in-house method validated by FRL. The edible portion of the raw food samples was rinsed with distilled water if necessary. Prepackaged and ready-to-eat (RTE) items were analysed directly as purchased. Food samples were weighed and the volume of those in fluid form (e.g., liquid milk, soymilk) were recorded before homogenisation. After enzymatic digestion, the sample was extracted by tetramethylammonium hydroxide. The extract was subsequently analysed by an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer.

4.3 Data analysis

17. The data on iodine content in food was reported as μg/100g (including products in fluid form after considering their density) of edible portion, rounded to 2 significant figures. Values below the limit of detection (LOD) (i.e., 0.2μg/100g) were reported as Not Detected (ND). When calculating an arithmetic mean or median concentration of iodine in the same type of food, where appropriate, the ND results were allocated to 0.1μg/100g (i.e., half of LOD).17

18. Both the mean and median values were provided at the food item level, whereas the minimum and maximum values were provided for all food groups and food items.

5 Results and Discussion

5.1 Iodine contents in food groups and food items

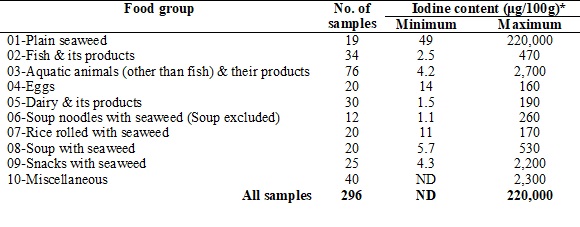

19. Except for one beverage sample, all 295 samples (99.7%) were detected with iodine at least above LOD. The iodine contents of the collected samples varied a lot among different types of foods (e.g., plain seaweed and eggs) and within the same type of food (e.g., fresh/hydrated seaweed). Similar to the RA Study 2011, a large variability of iodine contents was found in foods belonging to the same group. The ranges of iodine contents of the 10 groups of foods are summarised in Table 2. Details of individual food items are shown in Appendix.

Table 2. Iodine level in food samples by food group (μg/100g)

* Data are rounded to 2 significant figures.

20. Results showed that the iodine contents ranged from ND to 220,000μg/100g. The overall iodine content in the first five groups was comparable to that reported in the RA Study 2011. The observation of wide variations in iodine content in the same type of food samples in this study was generally in line with overseas studies and the literature. The wide variations may be due to several reasons: (i) for food samples such as raw eggs, raw seawater fish, plain seaweed, their iodine contents can fluctuate widely due to their species, the feeds used and mode of farming practices, the habitat, seasonal variation, etc., (ii) for other food samples such as soup noodles, desserts, beverages, and biscuits, their iodine contents can vary significantly owing to the quantity of iodine-rich ingredients added.

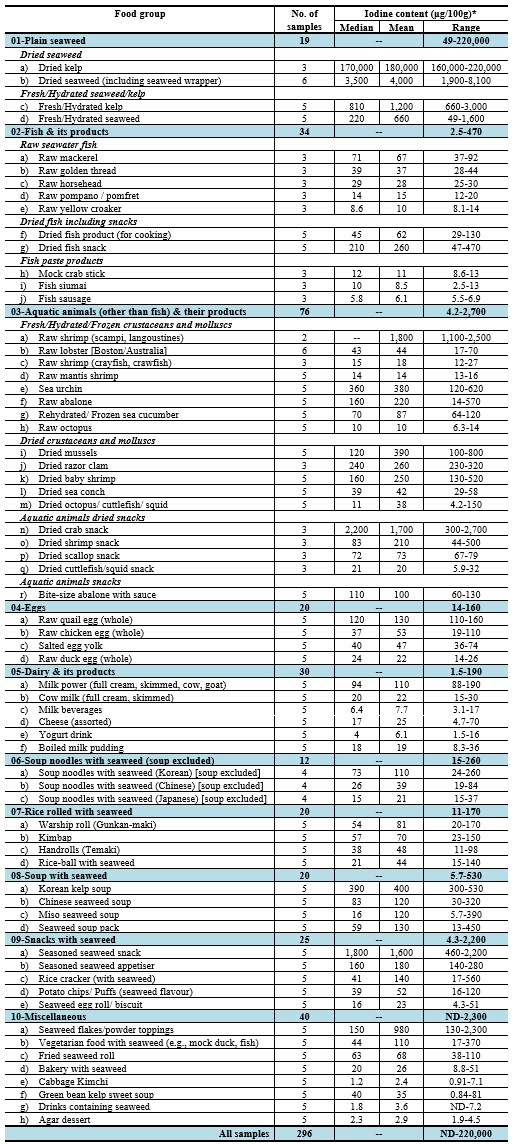

21. Based on the mean values, the food group “Plain seaweed” outstands the others as almost all of its food items contain iodine above 600μg/100g. It is followed by the food group “aquatic animals (other than fish) & their products”, with nearly half of its food items containing iodine above 200μg/100g. Furthermore, the top five food items with the highest iodine content (in descending order) per 100g are: (1) Dried kelp (180,000μg); (2) Dried seaweed (including seaweed wrapper) (4,000μg); (3) Dried crab snack (1,700μg); (4) Seasoned seaweed snacks (1,600μg); and (5) Seaweed flakes/powder toppings (980μg).

5.2 Consume more seaweeds, seafoods, eggs and dairy products in the balanced diet to increase iodine intake

22. In this study, most plain seaweed, including dried and fresh/ hydrated kelp and seaweed have very high iodine levels (ranged 49-220,000µg/100g). For dried kelp and dried seaweed (including seaweed wrapper), the median iodine concentrations are 170,000 and 3,500µg/100g (mean 180,000 and 4,000µg/100g), respectively. Some fresh/hydrated kelp and seaweed sample contained iodine levels above 1,000µg/100g. As revealed in the RA Study 2011, given that most of the iodine (about 80%) in kelp or seaweed will dissolve into the soup after boiling, consumers are reminded to take this into consideration when adding kelp or seaweed in the cuisine to increase their iodine intake.

23. Dried seaweed or seaweed extracts are often found in foodstuffs. Iodine content can be extremely variable depending on seaweed species, bioavailability, and losses in cooking. Consuming seaweed alone or as a dietary supplement is unlikely to be harmful if taken occasionally (once or twice a week).18 That said, taking too much iodine exceeding the tolerable upper limit for a prolonged period may affect the thyroid function. The WHO reported that for healthy iodine-replete adults, daily iodine intakes of up to 1,000μg appear to be entirely safe,4 which is similar to 0.017mg/kg body weight as evaluated by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives.19

24. Fish, crustaceans, and molluscs accumulate iodine from seawater, and the iodine levels vary with different species. Using a fillet (90g) of “raw mackerel” the seawater fish with the highest median iodine content (71µg/100g) as an example, a healthy adult consuming it will meet 43% daily iodine requirement. Using “sea urchin” (median 360µg/100g) as an example, a healthy adult consuming about 20g of it will meet 48% daily iodine requirement.

25. Based on the 2nd FCS, Hong Kong adults in general (all respondents) consume less than 20g of seawater fish (including coral fish) and less than 15g of crustaceans and molluscs daily. Thus, if the public could consume more seawater fish, crustaceans, and molluscs as part of their balanced diet, the overall iodine status of the population will be improved.

26. Eggs have different iodine levels, possibly due to the types of poultry and their feeds; they are generally good sources of iodine especially if the hen’s feeds are iodine-fortified. Moreover, dairy (e.g., milk powder) and dairy products (e.g., cheese; boiled milk pudding) could be good sources of iodine, especially when the milk comes from cows or goats with iodine feed supplements, and if iodophor sanitising agents were used to clean the cows and milk-processing equipment.20 Eggs, especially quail eggs, have rich iodine content and are adaptable in a wide range of tastes and dietary preferences. Consumers may consider including eggs in their cuisine or snack lists to increase iodine intake.21 Moreover, if they could consume more milk and dairy products in a balanced diet, their iodine intake would meet the daily requirement more easily.

27. Based on the 2nd FCS, Hong Kong adults in general (all respondents) consume about 26g of eggs and egg products (95% were chicken eggs) daily, i.e., about half a chicken egg or 2.5 pieces of quail eggs (one weighs about 10g). The current study shows that the median iodine levels for these amounts of chicken eggs or quail eggs are about 10µg and 30µg, respectively, which meets 7% and 20% of the daily iodine requirement, respectively. On dairy products, the result shows that drinking a glass (240ml) of “cow milk” (median 20µg/100g) will provide 48µg iodine (i.e., 32% daily iodine requirement), whereas a bowl (200g) of “boiled milk pudding” (median 18µg/100g) will provide 36µg iodine (i.e., 24% daily iodine requirement). Based on the 2nd FCS data, Hong Kong adults in general (all respondents) consume about 25g/day milk and dairy products, of which about 79% (about 20g) are from milk, milk beverages, and dried milk.

5.3 Other food one could consume to increase iodine intake

28. Among the different food groups tested in this study, the iodine contents reflect the types (e.g., seaweed or kelp, eggs, fish) of the iodine-rich source ingredients and their amounts present in each food item. Overall, the food samples covered in the current study are good sources of iodine.

29. For foods that could be consumed as a main meal, their daily iodine contribution could be significant. For example, compared to other types of Asian soup noodles, “Korean soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)” has the highest iodine content (median 73µg/100g) in the “Soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)” group, probably due to the use of kelp instead of seaweed. In the “Rice rolled with seaweed” group, the amount of seaweed sheet used on “Kimbap” (median 57µg/100g) and “Warship roll (Gunkan-maki)” (median 54µg/100g) will affect their iodine content greatly. For these three items, consuming a bowl (200g) of “Korean soup noodles with seaweed (Soup excluded)”, a portion (250g each) of “Kimbap” or “Warship roll (Gunkan-maki)” will meet about 97%, 95% and 90% daily iodine requirement, respectively.

30. In the “Soup with seaweed” group, “Korean kelp soup” has the highest iodine content (median 390µg/100g) as compared with the other soups, probably because of the kelp used instead of seaweed. Kelp used as an ingredient in the “Green bean kelp sweet soup”, as reported in the “Miscellaneous” group could also explain its high iodine content (median 40µg/100g). Generally healthy adults consuming a bowl (200g) of “Chinese seaweed soup” (median 83µg/100g) (i.e., 111% daily iodine requirement) could obtain sufficient iodine (i.e., between 150 and 1,000µg) for a day, assuming their dietary iodine only comes from the soup.

31. More and more snacks and bakery wares added seaweed as ingredients (e.g., RTE seaweed, appetiser, biscuits, potato chips, etc.) are available in the market, as reported in the “Snacks seaweed” group and the “Miscellaneous” group. Consumers could consider including them as part of the balanced diet to increase iodine intake. For prepackaged products, consumers could look for the different forms of seaweeds written on the product description, such as their ingredient list. For example, “Seasoned seaweed snack” (median 1,800µg/100g) could provide (i.e., 54µg) 36% daily iodine requirement for an adult in just a small piece (i.e., 54µg iodin in 3g). On the other hand, adding a small spoon of “Seaweed flakes/powder toppings” (median 150µg/100g) to the food (e.g., rice, noodles, salads) could provide 5% of an adult’s daily iodine requirement (i.e., 8µg iodine in 5g). For vegetarians who are egg, milk, or dairy intolerant, the data in the Appendix on “Vegetarian food with seaweed (e.g., mock duck, fish)” (median 44µg/100g) could provide them with options to increase their iodine intakes.

5.4 Limitations

32. This study measured foods that have been reported to contain high iodine levels or have important contribution to iodine dietary intakes as reported in the literature. As a supplement to the RA Study 2011, it has covered a variety of seaweed-containing foods in the local diet. Although more representative iodine content could be achieved with larger samples analysed, the finite time and laboratory resources of the study has excluded some food already tested high in iodine in the RA Study 2011 (e.g., oyster, scallop, white sauce).

33. Certain food items with iodine-fortificants (e.g., bread made of iodine-containing dough conditioners, or seasonings added with iodised salt) have not been sampled.22 The results of this study represented only a snapshot of the iodine levels in the selected locally available foods. Caution should be taken when comparing the results from different studies. Apart from the test methods adopted, other factors such as research methodology, sampling strategies, sources of food, LOD, etc. would affect the outcome of the studies.

6 Conclusions and Recommendations

34. In this study, almost all of the samples collected were detected with iodine above the detection limit. Iodine is present in many locally available foods. Their contents vary greatly within and among food groups, food sub-groups, and food items. Food high in iodine include seaweeds such as kelps, seafood such as fish and prawns, eggs, dairy, and their products. They have been used as ingredients in many local foods including, noodle dishes, rice dishes, soup dishes, bakery wares, snacks, desserts, beverages, seasonings, etc. Consumers can increase their iodine intake by adding high iodine ingredients or including high iodine food into their balanced diets. It is worth noting that kelps contain very high levels of iodine, so consume them in moderation. Persons with existing medical conditions or thyroid problems are advised to consult healthcare professionals concerning the intake of iodine.

35. The public is recommended to maintain a healthy and balanced diet and to consume foods that are rich in iodine, including seaweeds such as kelp; seafood such as fish and prawns; eggs; dairy; and their products, so as to meet the WHO’s daily iodine intake recommendation. According to the Joint Recommendation, members of public are advised to consume more iodine-rich food as part of a healthy balanced diet, and use iodised salt instead of ordinary table salt, keeping total salt intake below 5 g (1 teaspoon) per day. During food preparation, include iodine-rich ingredients to enhance the iodine content of different food (e.g., rice, noodles, soup, bakery, vegetarian food, beverages, desserts) in the diet. Examples of iodine-rich food or ingredients: seafood (e.g., seaweed/ kelp, seawater fish, crustacean, molluscs), eggs, dairy products. When choosing snacks, consider those containing high iodine content, like RTE seaweed, boiled quail eggs, and some dried seafood snacks (e.g., cuttlefish, shrimp, fish), etc..

References

- World Health Organization (2013). Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLiS): Iodine deficiency. https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/iodine-deficiency

- World Health Organization (2007). Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination: A guide for programme managers (3rd Ed.). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43781

- World Health Organization (2006). Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43412/9241594012_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization (2004). Chapter 16: Iodine. In Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition (2nd Ed.). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42716

- Iodine Global Network (Accessed on 3 March 2025). Global scorecard of iodine nutrition 2023. https://ign.org/scorecard/

- Hatch-McChesney A. & Lieberman HR. (2022). Iodine and iodine deficiency: a comprehensive review of a re-emerging issue. Nutrients. 14(17):3474. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9459956/

- World Health Organization (2013). Urinary iodine concentrations for determining iodine status in populations. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/85972/WHO_NMH_NHD_EPG_13.1_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization (2024). Call for authors - Systematic reviews urinary iodine as an indicator of iodine status and mapping of findings. https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/call-for-authors-systematic-reviews-urinary-iodine-as-an-indicator-of-iodine-status-and-mapping-of-findings

- Eriksson J. et al. (2023). Urinary iodine excretion and optimal time point for sampling when estimating 24-h urinary iodine. Br J Nutr; 13-(8): 1289-1297. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10511680/

- Department of Health, HKSARG (2021). Iodine Survey Report. https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/iodine_survey_report_en.pdf

- Department of Health, HKSARG (2023). Report of Population Health Survey 2020-22. https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/features/37474.html

- Department of Health, HKSARG (2023). Report of Population Health Survey 2020-22 (Part I). https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_1_report_eng_rectified.pdf

- Department of Health, HKSARG (2023). Thematic Report on Iodine Status (Population Health Survey 2020-22). https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_iodine_report_eng.pdf

- Centre for Food Safety, HKSARG (2011). Dietary Iodine Intake in Hong Kong Adults. https://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/programme/programme_rafs/programme_rafs_n_01_12_Dietary_Iodine_Intake_HK.html

- Chung S, Chan A, Xiao Y, Lin V & Ho Y. (2013). Iodine content in commonly consumed food in Hong Kong and its changes due to cooking, Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 6:1, 24-29. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19393210.2012.721011

- Centre for Food Safety, HKSARG (2021). The Second Hong Kong Population-based Food Consumption Survey. https://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/programme/programme_firm/programme_fcs_2nd_Survey.html

- World Health Organization (2020). Chapter 6: Dietary Exposure Assessment of Chemicals in Food. In Principles and methods for the risk assessment of chemicals in food (Environmental health criteria 240). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241572408

- Smyth PPA. (2021). Iodine, Seaweed, and the Thyroid. Eur Thyroid J, 10(2): 101-108. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8077470/

- World Health Organization (2021). Evaluations of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA): Iodine. https://apps.who.int/food-additives-contaminants-jecfa-database/Home/Chemical/2048

- Flachowsky G. (2018). Re: Eggs: harnessing their power for the fight against hunger and malnutrition. In Global Forum on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN Forum). https://www.fao.org/fsnforum/comment/9157

- National Institutes of Health (Updated 5 November, 2024). Iodine: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Iodine-HealthProfessional/

- Santos JAR. et al. (2019). Iodine fortification of foods and condiments, other than salt, for preventing iodine deficiency disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019(2): CD010734. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6370918/

Appendix: Iodine contents (μg/100g) detected in food samples

* Data are reported in 2 significant figures.